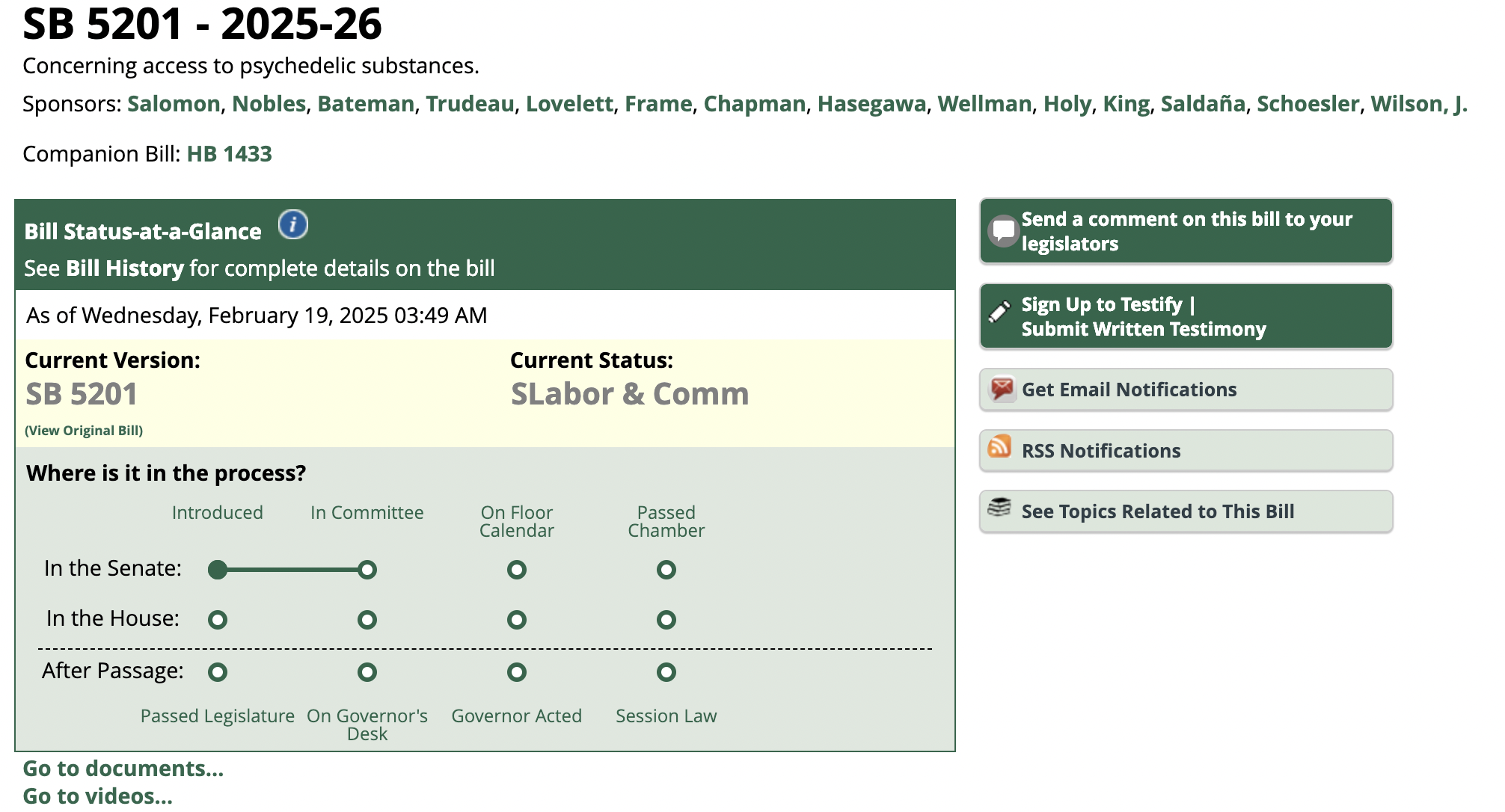

In November 2022, Colorado voters passed Proposition 122, the Natural Medicine Health Act (NMHA), which establishes a regulated natural medicine access program and provisions for personal use of natural medicines. Under this new law, Colorado will become the second US state – following Oregon – to issue licenses allowing the commercial production and administration of federally-illegal psychedelic substances. The state-licensed psychedelic programs follow in the footsteps of cannabis state legalization initiatives adopted by states across the country that, like the psychedelic measures, license and regulate conduct under state law that constitutes a crime under the federal Controlled Substances Act.

- Regulated Psilocybin Program in Colorado

Just like Oregon’s psilocybin licensing program, Colorado’s state-regulated program will provide participants with access to natural psychedelic substances under the supervision of a licensed facilitator. The NMHA tasks Colorado’s Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) with overseeing and adopting rules to govern the natural medicine access program, taking guidance from the Natural Medicine Advisory Board’s recommendations. There are two initial license types contemplated by the statute – Licensed Healing Centers and Licensed Facilitators – but additional licenses and registrations may be created by DORA.

Although Colorado’s NMHA uses words typically associated with the medical and pharmaceutical industries – “medicine,” “health,” “treatment,” “recovery,” and “healing” – it does not contemplate any involvement of medical doctors. Instead, Colorado’s law – like Oregon’s– will allow all people 21 years of age or older to purchase and use psychedelics, without the recommendation or approval of any doctor or other health care professional.

Colorado’s program will start with psilocybin and psilocin, but may be expanded after June 1, 2026 to include one or more of the other substances identified in the definition of “natural medicine”: DMT, ibogaine, and mescaline (but not mescaline extracted from peyote).

The definition of a “healing center”is broad and purposefully flexible.

(d) “HEALING CENTER” MEANS AN ENTITY LICENSED BY THE DEPARTMENT THAT IS ORGANIZED AND OPERATED AS A PERMITTED ORGANIZATION:

(I) THAT ACQUIRES, POSSESSES, CULTIVATES, MANUFACTURES, DELIVERS, TRANSFERS, TRANSPORTS, SUPPLIES, SELLS, OR DISPENSES NATURAL MEDICINE AND RELATED SUPPLIES; OR PROVIDES NATURAL MEDICINE FOR NATURAL MEDICINE SERVICES AT LOCATIONS PERMITTED BY THE DEPARTMENT; OR ENGAGES IN TWO OR MORE OF THESE ACTIVITIES;

(II) WHERE ADMINISTRATION SESSIONS ARE HELD; OR

(III) WHERE NATURAL MEDICINE SERVICES ARE PROVIDED BY A FACILITATOR.

There is a lot to unpack here, but suffice it to say, psychedelics can potentially be cultivated, sold, and consumed at any of a wide variety of locations under this definition. The NMHA also directs DORA to establish rules that will allow for psychedelics to be administered in “another location” that is not a designated healing center, “as permitted by rules adopted by the Department.” Such locations could potentially include private residences, other types of health-care facilities, and outdoor natural settings. With that said, we will see how the framework and boundaries take shape with the creation of the rules, which are scheduled to be adopted in 2024.

There will be training programs for facilitators and certain education and qualification requirements. Licensing for facilitators will be tiered, so as to provide for varying levels of education and training depending on the participants the facilitator will be working with and the services.

- Personal Use Now

Part of the NMHA removed criminal penalties for the personal use of natural medicine for persons 21 years of age or older. The personal use section is separate from the regulated natural medicine access program in the NMHA. Think of the NMHA as having two parts – one is the regulated natural medicine program and the provision of natural medicine services; and the other is personal use. The personal use provisions allow for the cultivation, processing, storing, using, transporting, obtaining and ingesting of natural medicines, including dimethyltryptamine (DMT), ibogaine, mescaline (not from peyote), psilocybin and psilocyn, for personal use. There are some boundaries to this personal-use decriminalization written into the NMHA, which are summarized below.

– Retail sales are prohibited. There is no retail market provided for, or intended by the NHMA, outside of what is allowed in the context of licensed healing centers. Outside of the licensed healing centers, a person may still charge for bona fide therapy or harm reduction services, or other support services with a connection to natural medicine, but there can be no remuneration for the natural medicine.

– Personal use is not allowed for those under the age of 21. A person who is under 21 year of age will be subject to a drug petty offense for possession, use, transporting, sharing, natural medicine or natural medicine paraphernalia, subject only to a penalty of more than four hours of drug education or counseling provided at no cost to the person.

– There is no cultivation or consumption permitted in schools, detention centers, public spaces or federal lands. Keep in mind that the natural medicines under NMHA are still schedule I substances, and are still federally illegal.

– People are not allowed to give away any amount of natural medicine as part of a business promotion or other commercial activity,

– People are not allowed “to permit paid advertising related to natural medicine, sharing of natural medicine, or services intended to be used concurrently with a person’s consumption of natural medicine.” It is unclear how, or whether, this provision would apply to any advertising done in connection with licensed psilocybin healing centers.

The takeaway here is that the intent for personal use under the NMHA is to provide individuals with additional options for their mental health and spiritual growth, and to remove penalties associated with indigenous and traditional uses.

In practice, most people who use psychedelic substances acquire them from other people, whether or not any compensation exchanges hands. Outside the context of licensed healing centers, any such transactions will continue to be prohibited, although the decriminalization of personal possession and use will likely result in fewer overall prosecutions, and a de-emphasis on prosecution of lower-level transactions.

- Colorado’s NMHA differs in notable respects from Oregon’s Psilocybin Services Act

There are several differences between Colorado’s NMHA and Oregon’s Psilocybin Services Act. A few salient points of comparison are outlined below.

Under Oregon’s Psilocybin Services Act, psilocybin may only be administered in licensed service centers. The effect is that the number of service centers will be limited and that limitation in turn reduces options and may increase costs. On the other hand, Colorado’s NHMA allows for the provision of psilocybin services outside of licensed healing centers and specifically contemplates natural medicine services being provided in places such a residential homes, community mental health centers, long-term care facilities, or other types of facilities where health care is provided. There is purposeful flexibility worked into the NMHA with regard to where natural medicine services may be provided. As the regulations are being developed, we will see exactly how this will look, but the hope is to create opportunities for equitable access to natural medicines.

Another difference is that Colorado does not have a residency requirement written into the NMHA. We previously wrote about Oregon’s requirement that psilocybin businesses be majority-owned by Oregon residents here.

Oregon’s psychedelics program is limited to the licensing and regulation of psilocybin activities. Colorado’s program, however, expressly contemplates extending the licensing program to cover the distribution and administration of three other psychedelic substances: DMT, ibogaine, and certain forms of mescaline.

Colorado’s NMHA contemplates that licensed healing centers will be allowed to cultivate and manufacture psychedelic substances in addition to administering them to adults. Oregon, by contrast, has separate license types for psilocybin manufacturers and psilocybin service centers, contemplating that many businesses may focus on either manufacturing or administration, and will not be a single vertically-integrated organization.

Colorado’s NMHA decriminalizes the personal possession and use of various psychedelic substances, while Oregon’s psilocybin licensing program did not address personal use of psilocybin outside the context of licensed service centers. Oregon, however, passed a law in November 2020 (Measure 110) decriminalizing the possession for personal use of small amounts of all controlled substances, making such conduct civil infractions punishable only by citation and a $100 fine (which can be waived by calling a hotline to screen for substance use disorder).

Finally, the Oregon Psilocybin Services Act provided an out for local jurisdictions whose residents did not want to participate in the program. As such, many cities and counties opted out of the program in this past November’s election. Conversely, under Colorado’s NMHA, a local jurisdiction may not completely prohibit the establishment or operation of a healing center. Localities can, however, enact reasonable ordinances and regulations so long as they do not conflict with NMHA, and thus will have the practical ability to make it difficult for psychedelic businesses to operate.These are just a few points and only skim the surface in the comparison of the two programs. As Colorado gets moving on discussing the regulations, we will see start to see the program take shape.

- Will it be like the cannabis industry?

Yes and no.

While both industries contemplate a state-regulated program or industry that is illegal under federal law, one major difference is that the NMHA is not intended to create an open retail market like we are all familiar with in the cannabis industry. The intention of the NMHA is to create a program for the supervised use of natural medicines, starting with psilocybin or psilocin, but the NMHA does not contemplate a dispensary model, or retail sales outside the context of supervised use.

On the similarity side, interested parties hoping to enter this new ecosystem of natural medicine and natural medicine services will face barriers similar to those that the cannabis industry confronted. The common denominator between the two industries is the fact that cannabis and psilocybin are both listed on schedule I of the federal Controlled Substances Act. Therefore, psilocybin businesses will face issues with taxes (280E), access to banking (or lack thereof), buying or leasing property for the business (cost, lease agreements, etc.), obtaining insurance, and securing federal trademark protection. As with cannabis businesses, absent a change in federal law, everyone participating in Colorado’s licensed psychedelic industry will also face the continuous threat of federal criminal prosecution and asset forfeiture, even if operating in full compliance with state laws.

- What is coming up?

The first date to keep in mind is January 31st. By then, the Governor of Colorado will have hopefully appointed the members of the Natural Medicine Advisory Board, who will be drafting recommendations for the regulations, to provide to DORA.

Next, by September 2023, we will hopefully see recommendations from the Natural Medicine Advisory Board for DORA’s eventual rules, as well as recommendations related to research, training, product safety, harm reduction, cultural responsibility, and requirements to ensure that the regulated natural medicine access program is equitable and inclusive, just to name a few.

Then, by a year from now, DORA is expected to adopt rules that establish the qualifications, education, and training requirements that facilitators must meet before providing natural medicine services and to approve any required training programs.

Finally, by September 30, 2024, the rules governing the program should be adopted and DORA will open its doors to accepting applications, which by law are to be processed and approved or rejected within 60 days of submission.

In the meantime, interested parties can participate in the rulemaking process, work on developing a corporate structure and business plan, engage with local officials and community groups regarding zoning and other local considerations that may impact psychedelic businesses, and start discussions with their CPA or accountant on a tax strategy.

Psychedelics

Cannabis News2 years ago

Cannabis News2 years ago

One-Hit Wonders2 years ago

One-Hit Wonders2 years ago

Cannabis 1012 years ago

Cannabis 1012 years ago

drug testing1 year ago

drug testing1 year ago

Education2 years ago

Education2 years ago

Cannabis2 years ago

Cannabis2 years ago

Marijuana Business Daily2 years ago

Marijuana Business Daily2 years ago

California2 years ago

California2 years ago