Himal….

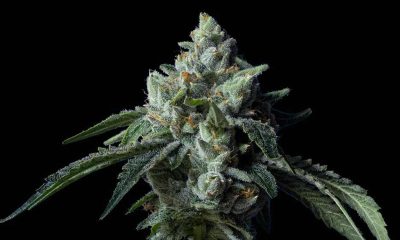

Some propose legalising marijuana production to ease Sri Lanka’s economic crisis. Yet, any move to legalise marijuana cultivation in Sri Lanka will have to overcome a long history of prohibition, social stigma and criminalisation

As Sri Lanka struggles with its worst economic crisis since its Independence, policymakers are increasingly focusing on diversifying the country’s export industries to bring in much-needed foreign exchange, to purchase essentials such as fuel and medicines. Within this context, presenting the budget for the year 2023, President Ranil Wickremesinghe announced the appointment of an expert committee to examine the possibilities of producing cannabis – locally referred to as kansa or ganja – for export purposes.

This echoes Sri Lanka’s state minister of tourism, Diana Gamage, who remains a strong advocate for legalisation and claims it will help the economy. She has earlier promised to bring in investments worth USD 2 billion for the cannabis plantation sector.

The state minister of indigenous medicines, Sisira Jayakody, in an interview stated that the expert committee has made progress and that the final draft of the legal amendments required to make cannabis available for ayurvedic exports has already been sent to the attorney general’s department. “Following the recommendations from the Attorney General, we hope to send it to the Cabinet of Ministers for approval. Once Parliament also approves, we can start this work,” Jayakody said. He further said that although both local and foreign investors had expressed their interest in cannabis cultivation in Sri Lanka, the government was yet to begin lengthier discussions with them due to legal barriers.

Sri Lanka remains strict on the use of cannabis for recreational and medicinal purposes, despite many tourist hotspots being popular havens for the consumption of cannabis and related products. While cannabis has been legalised in many countries, its cultivation and export remain controversial due to its history as an illegal drug and its potential for misuse. Further, exporting cannabis from Sri Lanka would require navigating a complex legal landscape and establishing proper regulatory frameworks to ensure compliance with both domestic and international laws. Additionally, the cultural attitudes towards drugs in Sri Lanka may pose challenges for the commercial cultivation of cannabis. Its association with illegal drugs will also make gaining acceptance for commercial cultivation difficult. Moreover, establishing a “profitable” cannabis industry in Sri Lanka will require significant investment in infrastructure, research and development, and regulatory frameworks. This includes setting up proper growing and processing facilities, implementing quality-control measures and developing a robust supply chain to ensure that products meet international standards., It is essential to examine these questions alongside the economic viability of exporting cannabis from Sri Lanka thoroughly.

A 300-year ban

Cannabis use for medicinal purposes has been recorded in Sri Lankan history for centuries. Some claim that early writings on cannabis date back as far as 341 CE, when King Buddhadasa of Anuradhapura wrote about it in his pharmacopoeia, Sarartha Sangrahaya. In fact, Wickremesinghe, in his address to Parliament, used the Sanskrit term for cannabis, “thriloka wijayapathra” meaning “victory over three realms”.

The head of the department of crop science at the University of Ruhuna, K K I U Arunakumara, states that there is written evidence about the historical use of cannabis in local medicine: “The kings write books about local medicine. Those books state that kansa is a very valuable drug.” Negative attitudes towards cannabis use in Sri Lanka can be traced back to the country’s colonial past. The Dutch introduced the ban on cannabis use in Sri Lanka in the 17th century, which the British colonial administration subsequently renewed. “After the Dutch, the British government also banned it,”Arunakumara states “That amendment by the British is still there in the law – no Sri Lankan government has banned it. Kansa was banned because it was used. It was used because it was cultivated in the country. We can conclude then that historically, kansa was cultivated, and reasonably believe that it was at a level where it could have been exported.”

Exporting cannabis from Sri Lanka would require navigating a complex legal landscape and establishing proper regulatory frameworks to ensure compliance with both domestic and international laws.

“There are four names: kansa, ganja, cannabis and marijuana. When we call it kansa, there is a pleasantness, but that is not there when we call it ganja. People have forgotten how cannabis became ganja in Sri Lanka. There is a cultural context for this,” said Arunakumara, emphasising the need to change cultural attitudes towards cannabis by highlighting its history.

“We need to tell people the truth. Only if there is successful acceptance from society can we eventually explore its uses in the local market too,” he added.

Cannabis use in Sri Lanka has been stigmatised and continues to be seen as a social and moral issue. The National Dangerous Drugs Control Board (NDDCB) has reported that, in 2021, cannabis was the most commonly used illicit drug in Sri Lanka, with an estimated 301,898 users. The NDDCB states that as of 2020, nearly two percent of the population above age 14 used cannabis as a drug in the last 14 years.

According to the NDDCB, in 2021, the Police Narcotics Bureau recorded that possession of cannabis and Kerala cannabis led to the second and third highest percentages of drug-related arrests, after those linked to heroin. In fact, of the total 110,031 drug-related arrests in 2021, 30 percent were for cannabis possession. The grouping of cannabis with other, more dangerous drugs, such as heroin, coupled with blanket criminalisation, contributes significantly to the stigma surrounding cannabis.

Read full article

Sri Lanka’s woes with cannabis legalisation

Cannabis News2 years ago

Cannabis News2 years ago

One-Hit Wonders2 years ago

One-Hit Wonders2 years ago

Cannabis 1012 years ago

Cannabis 1012 years ago

drug testing1 year ago

drug testing1 year ago

Education2 years ago

Education2 years ago

Cannabis2 years ago

Cannabis2 years ago

Marijuana Business Daily2 years ago

Marijuana Business Daily2 years ago

California2 years ago

California2 years ago