Cannabis Canada

Mushroom Dispensaries in Canada

Published

2 years agoon

By

admin

Are there really ten mushroom dispensaries across Canada?

In Montreal, there’s at least one. Or there was. Hours after opening this past Tuesday, police raided the FunGuyz mushroom dispensary. According to a police spokesperson, they arrested four people.

However, a store spokesperson told the Canadian Press the raid was a “waste of taxpayers’ money” and that they expect to open the next day.

This isn’t the first raid FunGuyz has experienced. On July 6, police raided their Windsor, Ontario location.

FunGuyz co-owner Edgar Gorbans told the local news: “We’re clearly pro legalization. We just hope that having these stores will draw some attention to the topic of psilocybin and the problems that are involved in accessing psilocybin.”

Mushroom Dispensaries in Canada

The Windsor store was up and running hours after being raided, according to Gorban. He says FunGuyz has ten other stores across the country.

The goal is to provide medicinal psilocybin to help Canadians.

“We’re just getting started and we hope that the word gets out,” he told CTV.

Currently, Canadians can only access psilocybin, not through a mushroom dispensary, but through the Special Access Program (SAP).

The SAP isn’t without its criticisms. Long wait times, bureaucratic hurdles, and a low probability of approval frustrate Canadians of all ailments.

Adding insult to injury, it’s easier to apply (and get approved) for MAiD, the government suicide program.

Gorban’s civil disobedience is entirely justified. The psilocybin buck does not stop with Health Canada. A handful of politicians and bureaucrats do not have intrinsic rights to your body.

And if there’s any lesson from cannabis legalization, it’s that “illegal” dispensaries work. All power to mushroom dispensaries in Canada.

Mushroom Dispensaries Menu

The FunGuyz mushroom dispensary in Montreal, Canada offered customers seven types of 14 and 28-gram bags. Bags of dried mushrooms labelled names such as “African Pyramid” or “Blue Meanie” lined the shelf.

There was also a microdose option, offering psilocybin in 50, 100, and 200 micrograms.

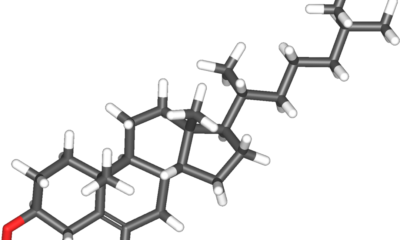

People consume psilocybin mushrooms for a variety of reasons, whether recreational or medicinal. It can provide feelings of euphoria and sensory changes that can be pleasant or helpful for one’s psyche.

A landmark study from the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research found psilocybin to be safe and positive.

Psilocybin works by activating serotonin receptors. This can affect mood, cognition, and perception. Although, “set and setting” apply here.

Ritual use of psilocybin dates back to pre-Columbian Mesoamerican societies. The practice continues to this day.

Recently, doctors have tested psilocybin for treating depression, end-of-life anxiety, social phobias, and even cluster headaches. While mushroom dispensaries in Canada are not legal, you can technically access psilocybin for these ailments.

Indeed, the evidence linking psilocybin-induced hallucinations and positive therapeutic outcomes grows every year.

What’s Next for Psilocybin in Canada?

Gorban told the news: “We’re trying to provide access to psilocybin that the government can’t.” He has vowed to launch a constitutional challenge.

With legal cannabis nationwide and decriminalized drugs in B.C., the continued prohibition of psilocybin mushrooms makes no sense.

Only religions and cults try to control people’s minds. So-called “liberal” governments should butt out. An individual’s mind and body are sovereign.

Mushroom dispensaries in Canada should be as common as Tim Horton’s.

You may like

-

The road ahead for cannabis lending in 2025

-

Cannara Biotech Announces Appointment of Justin Cohen to Board of Directors

-

Can Marijuana Help Cholesterol – The Fresh Toast

-

Safe Cannabis Consumption During Wildfire Season

-

Food Asphyxiation Is Way More Dangerous Than Cannabis

-

Outdoor Marijuana Grows Are Better All The Way Around

All about Cannabis

B.C. Court Dismisses Cannabis Retail Lawsuit – Cannabis | Weed | Marijuana

Published

2 years agoon

September 22, 2023By

admin

A British Columbia (B.C.) court dismissed a lawsuit from owners of licensed cannabis retail shops. Last year, this group of cannabis retailers sued the province for not enforcing cannabis regulations.

While licensed cannabis retailers jump through bureaucratic hoops and pay excessive taxes on the faulty premise that this contributes to “public health and safety,” the B.C. Bud market of “illicit” retailers doesn’t face these same hurdles.

Particularly on Indigenous Reserves, where the plaintiffs claim damages of at least $40 million in lost revenue.

Justice Basran considered whether the province owed the plaintiffs a private law duty of care in this context. The plaintiffs claimed the province committed torts of negligence and negligent misrepresentation.

But what does this mean? And was Justice Basran’s dismissal of the lawsuit justified?

Details of the Plaintiff’s (Cannabis Retail) Argument

While the cannabis retailers suing the province wished to remain anonymous, CLN uncovered who they were. Their position is understandable. The government sold them a bill of goods.

When Canada legalized cannabis, the province of B.C. effectively said, “play by the rules and you’ll profit.” The reality has been anything but.

Obviously, licensed cannabis retailers are at a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis the unlicensed cannabis shops.

So why did Justice Basran dismiss the lawsuit?

First, let’s look at what the plaintiffs claimed in their suit. What do “torts of negligence” and “negligent misrepresentation” refer to in this context?

Tort Law

Negligence is a fundamental concept in tort law. It means a failure to exercise a degree of care reasonable people would exercise in similar circumstances.

To establish a claim of negligence, the plaintiff (in this case, a group of licensed cannabis retailers) needed to prove the following:

- That the province of B.C. owed a duty of care to the licensed cannabis retailers.

- That the province breached that duty by failing to meet the standard of care expected under the circumstances (i.e. The province’s cannabis enforcement authority should have been raiding unlicensed shops more than they were)

- That the province’s breach of duty directly caused harm or damages (i.e. Causation) to the licensed cannabis retailers

- And that these actual harms (or losses) result from the province’s breach of duty.

The plaintiffs alleged that B.C. failed to enforce cannabis regulations (specifically, the Cannabis Control and Licensing Act) on Indigenous Reserves. They claimed this negligence resulted in damages of at least $40 million.

Negligent misrepresentation is a specific type of negligence claim that arises when one party provides false or misleading information to another party, and the party receiving the information relies on it (to their detriment).

To establish negligent misrepresentation, the licensed cannabis retailers had to prove the following:

- That the province made a false statement, whether intentionally or not

- That the plaintiffs relied on this false statement

- The plaintiffs suffered financial (or other) losses from relying on this false statement.

In this case, the plaintiffs said that B.C. promised them a viable, legal, above-the-board retail cannabis industry. One way of ensuring this would be to take enforcement action against unlicensed retailers, whether on Indigenous Reserves or not.

Did the B.C. Government Owe a Duty of Care to the Cannabis Retailers?

Justice Basran considered whether the province owed the plaintiffs a private law duty of care. The B.C. government argued that it did not owe such a duty because the parties had no direct relationship.

But what does this mean?

In tort law, a “duty of care” is a legal obligation imposed on an individual (or group, entity, etc.) to exercise reasonable care and caution to prevent harm to others affected by their actions and omissions.

Of course, not all actions or omissions give rise to a duty of care. That’s where proximity comes in, which refers to the direct relationship between the parties. In this case, whether a direct connection between the province’s cannabis regulators and the cannabis retailers justifies imposing a legal duty.

Justice Basran had to determine whether the province of B.C. owed a “private law duty of care” to the cannabis retailers. Of course, B.C. argued that it did not. They argued that their duty was the “public interest,” not the economic interests of specific businesses.

Justice Basran agreed that no duty of care existed due to lack of proximity.

How Did the Court Come to this Decision?

Justice Basran dismissed the B.C. cannabis retail lawsuit based on the “plain and obvious” legal standard used when deciding to strike pleadings.

The court considered the Anns/Cooper test to determine whether a duty of care existed. This involves two stages. First, whether the harm alleged was reasonably foreseeable. And second, whether there is a close relationship between the parties (proximity).

Justice Basran found no prima facie duty of care between the province and the licensed cannabis retailers. The court argued that B.C.’s cannabis regulations do not establish a legislative intention to create such a duty.

The court also ruled that the claims made by the province (i.e. Get licensed and profit) did not create a sufficient relationship to impose a duty of care.

Suppose the court had recognized that such a duty exists. Justice Basran was concerned such a decision could result in more of these types of lawsuits where the province (and its regulators) are held liable for the economic losses of numerous businesses due to their incompetence.

Justice Basran weighed the potential negative consequences of such a decision and decided it wouldn’t be in the best interests of the legal system, taxpayers, or society as a whole to impose such a duty.

B.C. Court Dismisses Cannabis Retail Lawsuit

A B.C. court has dismissed the cannabis retail lawsuit. The decisions sound as if what’s convenient for the government overrules what’s just and fair.

Was Justice Basran’s dismissal of the lawsuit justified? Judges are, after all, only human. And there is an appeals court. So, there may be more to the case in the future.

In the meantime, to argue that judges in Canada have far too much power, that they are, in effect, legislating from the margins is considered a “far-right” viewpoint.

But there is nothing “far-right” or even “far-left” about upholding the values that underpin our rule of law.

Suppose governments can evade the consequences of their actions because of the potential cost to taxpayers or the legal system. In that case, there is no rule of law.

It’s rule by fiat masquerading as a rule of law.

All about Cannabis

Is Tilray Too Dangerous? – Cannabis | Weed | Marijuana

Published

2 years agoon

September 20, 2023By

admin

“Tilray is too dangerous,” said CNBC’s “Mad Money” host Jim Cramer. “It is a spec stock that is losing money, and we don’t recommend stocks that are losing money.”

Cramer isn’t the only one shying away from the Canadian cannabis producer. Kerrisdale Capital called the company a “failing cannabis player” in a recent report.

We are short shares of Tilray Brands, a $2.4bn failing Canadian cannabis player running a familiar playbook for unsuccessful businesses trading in the public markets: given structurally unprofitable operations, the company has resorted to ongoing, shameless and massive dilution to stay alive, even as management compensates itself generously while operating metrics further deteriorate.

But is this true? Is Tilray a failing cannabis player? Is Tilray too dangerous for investors?

CNBC is not a Reputable News Organization

Of course, CNBC is not a reputable news organization. It’s corporate press, the entertainment division of the military-industrial complex.

Likewise, Jim Cramer has been wrong so many times that it’s surprising people still take him seriously.

But Kerrisdale Capital doesn’t share Cramer’s reputation. Following their report, Tilray’s shares dropped 12% to around $2.75 per share.

Of course, it’s not all Kerrisdale’s fault. The other week, Tilray requested shareholders approve raising common stock shares from 980 million to 1.208 billion.

Tilray argues that the dilution is necessary to remain flexible in response to market uncertainty. But, as indicated by declining stock prices, shareholders weren’t happy.

But is Tilray too dangerous for investors?

Among Canadian cannabis producers, Tilray stands out as the dominant player, having succeeded where others have failed. Its global presence in pharmaceuticals and craft beer industries bodes well for future cannabis distribution.

But if Tilray is diluting its share to mask its fiscal health, is the company too dangerous to invest in?

Is Tilray Too Dangerous?

Kerrisdale Capital’s report isn’t a single-page newsletter. It’s a comprehensive takedown of Tilray’s fiscal and operational health. But is it accurate? Is Tilray too dangerous for investors?

“Tilray has a dilution problem,” the report reads. It refers to Tilray’s cash payments to a partner named Double Diamond Holdings. These are “recurring cash obligations” that Tilray has been increasingly using its stock for payment.

This means Tilray is giving away ownership to fulfill its financial obligations.

Likewise, the report highlights that these payments have grown from $24 million in cash to $100 million in shares. The report suggests Tilray is undervaluing its stock when making these payments to Double Diamond Holdings.

The report also criticizes Tilray for not being transparent about these payments during their quarterly calls.

Kerrisdale Capital calls the adjusted EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) and free cash flow figures provided by Tilray “materially misleading.”

They criticize how these stock payments are missing from Tilray’s definition of free cash flow. The report says if you strip away “accounting gimmicks” and “other one-time benefits,” Tilray’s underlying financial performance is not improving but steadily (and significantly) deteriorating.

What About Craft Beer & USA Legalization?

Kerrisdale Capital’s report is critical of how rescheduling cannabis in the United States might benefit Tilray. It’s less of a question of “Is Tilray too dangerous,” and more of “Is this relevant to Tilray’s success?”

Or even detrimental to it?

The report suggests rescheduling cannabis to Schedule III will benefit pharmaceutical companies looking to patent cannabis-based FDA-approved drugs. There are also tax benefits for state-level operators.

But since Tilray doesn’t have significant U.S. cannabis operations, what benefit is there? Consider that rescheduling favors U.S.-based companies. It’s a net negative for a Canadian cannabis company like Tilray as it empowers its competitors with no tangible benefit to themselves (like cross-border trade).

The report also criticizes Tilray’s acquisition of brands from beer giant Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI). Kerrisdale Capital says the acquisition lacks strategic clarity, and the lack of financial details about the purchase is a huge red flag.

And it gets worse.

According to Nielsen data, the retail sales of these acquired brands have been declining. Looking at the numbers, it appears ABI was happy to sell off its lackluster brands.

Do Investors Consider Tilray Too Dangerous?

Is Tilray too dangerous? Is the company diluting its stocks to mask its financial health and maintain operations? If you’re a Tilray fan, consider taking a second look, suggests Kerrisdale Capital’s report.

While Tilray’s rationale for acquiring ABI brands was for future distribution into the THC-infused beverage market, Kerrisdale Capital’s report questions this logic.

They argue that the brands require significant investment, marketing and distribution. Without the support of ABI, Tilray has created more work for themselves. Exploiting the distribution opportunities is not as cut-and-dry as Tilray has made it sound.

Likewise, the report expresses concern about Tilray’s valuation, even before the news about rescheduling cannabis spiked their shares.

The report points out that on the news of a potential rescheduling, Tilray’s shares were trading 36 times higher than their EBITDA and three times higher than their revenue.

But ultimately, the report is concerned about near-term dilution risk related to refinancing. It mentions the payment patterns to Double Diamond. It suggests that over $40 million in stock will be paid to the supplier ahead of the $127 million in convertible notes set to mature on October 1.

Not exactly what you want to hear if you’re a Tilray shareholder. Which brings us back to our central question: Is Jim Cramer right? Did Kerrisdale Capital hit the nail on the head?

Is Tilray too dangerous?

All about Cannabis

What is Public Health? – Cannabis | Weed | Marijuana

Published

2 years agoon

September 19, 2023By

admin

What is “public health?” Since 2020, the term has entered the mainstream, but public health was around long before covid. Canadian politicians crafted cannabis legalization with “public health” goals in mind.

Instead of the traditional argument for legal cannabis, which is that you have a right to your body.

But let’s give them the benefit of the doubt. Like most things in life, let’s apply the 80/20 rule. 80% of “public health” are hapless bureaucrats who believe they are improving the world.

The other 20% are busybody control freaks.

They have the same mentality as the Temperance Movement or the Puritans. These people want to see more restrictions on the cannabis industry because some parents can’t be bothered to keep edibles out of their children’s reach.

These people want to bring back mask mandates despite the lack of evidence of their efficacy.

(If the meta-analysis of randomized control trials came out in favour of masking, we’d never hear the end of it, but because the conclusions didn’t support the narrative, the “fact checkers” have downplayed the study’s significance).

But what is public health? If governments must curtail our fundamental rights in the name of it, then we’ll need more than some broad, ambiguous term.

There is a Public Health Agency of Canada. They say their activities “focus on preventing disease and injuries, responding to public health threats, promoting good physical and mental health, and providing information to support informed decision making.”

But how accurate is this?

What is Public Health?

Is it like a public school? There are all kinds of schools, public and private. “Public” school refers to state-controlled and taxpayer-funded education.

Public school refers to a specific building or system, but “public education” or “public awareness” refers to government messages aimed at the general populace.

So, it’s clear that “public” means anything the state does. It’s a textbook example of doublespeak, in which “public” refers to two concepts.

For example, “public health” can refer to the general health of the Canadian public or the state-sponsored program of “public health,” which varies across different levels of government.

The point is to narrow the range of allowable thought. Suppose we identify public health with government bureaucrats. In that case, no one will seriously ask whether a lack of government “experts” results in better public health (that is, the public’s general health).

If it sounds confusing, that’s the point. That’s why Orwell wrote an entire book on the subject.

No, Really. What Is It?

What is public health? Let’s say it focuses on the well-being of entire communities or regions rather than individual health concerns. They focus on preventing diseases, injuries, and health threats. They do this through massive propaganda campaigns and political interventions.

You could extend the public health definition to food safety standards. Indeed, we consider cannabis, tobacco, and alcohol control the domain of “public health.”

Public health gathers and analyzes data to make reports and advise governments. Canada’s agency thinks “white supremacism” and “climate change” are some of the most significant factors affecting the health of Canadians.

Instead of, you know, cardiovascular diseases, which is Canada’s leading cause of death.

What About Exercise and Nutrition?

A conventional definition may include the promotion of healthy behaviours and lifestyles—things like exercise and nutrition. And indeed, exercise and nutrition are at the core of human health.

But, as was apparent during covid, “public health” doesn’t mean the general well-being of the populace. If that were the case, instead of demanding we place ourselves under house arrest, they would have promoted vitamin D consumption. (I.e. Go for a walk in the sun).

Likewise, obesity was an essential factor in determining whether covid would send you to the ICU. But did public health tell the public to stop consuming sugars and preservatives? To start exercising?

No, that would be “fat-shaming.” Obesity, when not part of the “body positivity” movement, is considered a disease that only pharma intervention can alleviate.

(Likewise, in 2020-21, speaking of “natural immunity” was like saying “Voldemort.” The only approved remedy to covid was an experimental jab that made pharmaceutical companies a lot of money).

If the “public health” experts are scratching their heads, wondering what’s happened to their credibility, then look no further than the inconsistent and corporate-friendly messaging.

We’ve researched who butters your bread, and we’re not happy. But, you know, blame the rise of “online right-wing extremism” instead. See where that leads you.

A Better Public Health

A better public health involves redefining what we mean by “public.” Instead of grouping everyone based on geography, better public health can cater to specific populations.

In essence, better public health prioritizes individual freedoms over collective interests. There is no genuine “collective” interest, just the spokesperson claiming to speak for “the people.”

A meaningful collective requires consent from all its members. And consent is only granted through voluntary association and exchange. The “social contract” justifying government authority is as concrete as the “divine right of kings” that excused monarchs.

“Implicit consent” – that we consent to public health just by living here – is also a poor argument. Applied to a different situation, and it’s justifying immoral actions based on the status of the victim.

In other words – “Of course, we gave her an ultimatum between experimental jabs and bringing home a paycheque. Look at what she was wearing! She was asking for it!”

Insomuch that the government is in the health business, its role should be minimal. Governments can “protect” people from direct harm by enforcing property rights and preventing fraud.

Leave the nutrition and exercise advice to experts who haven’t been bought off by pharma and large processed food manufacturers.

Any “public health” action that involves coercion – such as mandatory vaccinations, quarantine measures, and excise taxes – cannot be justified by typical ethical standards.

You and I can’t force people to behave a certain way under threat of imprisonment.

But this is precisely what “public health” is—part of the apparatus of compulsion and coercion. A better system sees the voluntarily-funded organizations of civil society play more significant roles.

Cannabis Decentralization

Canada never legalized cannabis based on people’s fundamental right to consume this non-lethal herb. The Trudeau government did it for “public health” reasons: to keep it out of children’s hands and crack down on organized crime.

This was all propaganda we routinely debunked. And at this stage in the game, the propaganda discredits itself.

But suppose there’s a small community somewhere in the prairies that doesn’t care for cannabis. They may not even care for alcohol. It may be a dry community with no weed or gambling, and everybody attends church every Sunday morning.

Why should their health information mirror that of a 20-something couple who live in their van, smoke weed and spend their time surfing and snowboarding?

Is “public health” a one-size-fits-all concept, or is this another example of the government’s forced egalitarianism?

How is it in the public’s interest to cap cannabis edibles at 10mg when producers and consumers want higher doses? Who is this “public” these so-called experts are protecting?

As with Canada’s cannabis legalization, or the covid restrictions and vaccine mandates, often the goal of “public health” isn’t to serve the public.

“Trust the Science” is another way of saying “Follow the Money.”

Whether it’s promoting planet-destroying corporate mono-crop agriculture (under the term “plant-based”), false links between cannabis and psychosis, or demanding you inject yourself with experimental pharma chemicals lest you lose your livelihood and thus food on the table and roof over your head.

Public health is a religion. A belief in Science™ and a method that justified lobotomies, Thalidomide, downplayed tobacco’s dangers and over-prescribed opioids.

What is “public health?” It is the enemy of the people.

The road ahead for cannabis lending in 2025

Cannara Biotech Announces Appointment of Justin Cohen to Board of Directors

Can Marijuana Help Cholesterol – The Fresh Toast

Safe Cannabis Consumption During Wildfire Season

Food Asphyxiation Is Way More Dangerous Than Cannabis

Outdoor Marijuana Grows Are Better All The Way Around

Shop 50% off at Story Cannabis this 420

Rolling Releaf: 420 deals delivered – all April long

Shop local this 420 at Simply Pure

25% off award-winning seeds from Fast Buds for 420

Distressed Cannabis Business Takeaways – Canna Law Blog™

United States: Alex Malyshev And Melinda Fellner Discuss The Intersection Of Tax And Cannabis In New Video Series – Part VI: Licensing (Video)

What you Need to Know

Drug Testing for Marijuana – The Joint Blog

NCIA Write About Their Equity Scholarship Program

It has been a wild news week – here’s how CBD and weed can help you relax

Cannabis, alcohol firm SNDL loses CA$372.4 million in 2022

A new April 20 cannabis contest includes a $40,000 purse

Your Go-To Source for Cannabis Logos and Designs

UArizona launches online cannabis compliance online course

Trending

-

Cannabis News2 years ago

Cannabis News2 years agoDistressed Cannabis Business Takeaways – Canna Law Blog™

-

One-Hit Wonders2 years ago

One-Hit Wonders2 years agoUnited States: Alex Malyshev And Melinda Fellner Discuss The Intersection Of Tax And Cannabis In New Video Series – Part VI: Licensing (Video)

-

Cannabis 1012 years ago

Cannabis 1012 years agoWhat you Need to Know

-

drug testing1 year ago

drug testing1 year agoDrug Testing for Marijuana – The Joint Blog

-

Education2 years ago

Education2 years agoNCIA Write About Their Equity Scholarship Program

-

Cannabis2 years ago

Cannabis2 years agoIt has been a wild news week – here’s how CBD and weed can help you relax

-

Marijuana Business Daily2 years ago

Marijuana Business Daily2 years agoCannabis, alcohol firm SNDL loses CA$372.4 million in 2022

-

California2 years ago

California2 years agoA new April 20 cannabis contest includes a $40,000 purse