Fantastic article and our must read of the week

45 years ago, foreign ministers of eight countries bordering the Amazon rainforest signed a treaty for Amazonian cooperation. The pact aimed to improve the lives of local populations by protecting natural resources and regulating their use. Almost half a century later, the Amazon region remains as a central stage for ecological exploitation and political violence. Meanwhile, the prohibition of cocaine fuels repeating episodes of brutality in the region, funding criminal enterprises’ actions.

This drug-related violence is particularly evident in Javari Valley, Brazil’s second-largest drug trafficking route, which is primarily used for the transportation of cocaine from Peru and Colombia to Brazil and other transatlantic markets. The capture of the region by organised crime syndicates like the Family of the North, the Red Command and the First Capital Command—organisations coming from the Northern states, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, respectively—are known to also contribute to deforestation, illegal mining, fishing and logging.

There are some that are concerned that Brazil might lose control over the Amazon to organised crime groups; but I believe that they are being overly optimistic by believing the region is under any sort of control in the first place. Like the other Amazonian countries, the Brazilian rainforest is not governed by state forces. And when it is not feasible to combat criminal syndicates, public security agents end up joining them. A set of questions that remains, though, even if they are rhetorical ones, are: is it really impossible to combat organised crime? Will the old strategy of deploying increasingly armed police and military forces to the region bring about a different outcome? Is there any other strategy that Amazonian countries could implement to change this scenario? For the two first questions, the answer is no. For the third one, however, there is a possible positive answer, and it should be the duty of decisionmakers to pursue all possibilities to address the potentially cataclysmic loss of the Latin American rainforest.

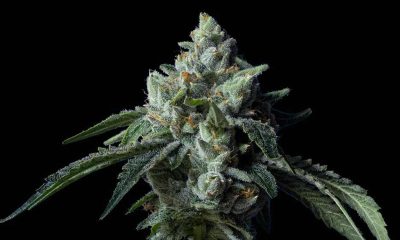

The salvation of the Amazon could lie in the legalisation and regulation of the production and sale of cocaine.

If there has ever been a time where Amazonian countries have the clout to lead on a global agenda to legalise cocaine, it is now. We have reached the stage where even the United Nations have recognised that it is not possible to build drug-free societies, preferring instead to focus on supply reduction and endorsing wider access to harm reduction services. We have lived to witness global publications like The Economist openly advocating for the legalisation of cocaine, a rational continuation of its past support for the legalisation of cannabis in 2013. We are living in a moment in which Gustavo Petro, the president of the country that produces the most cocaine in the world is willing to legalise it, recognising the historical futility of the prohibitionist approach, which has only exported drug harms from wealthy countries in the Global North to violent conflicts in the Amazon and beyond. One day after the inauguration of Brazilian President Lula for his third mandate, Colombian President Gustavo Petro posted a picture of the two of them together on his Twitter account. With it, he asked for a pact between the two countries to save the Amazon, including a call to transform both countries’ drug policies.

Read full article at

https://www.talkingdrugs.org/legalise-cocaine-to-save-the-amazon

Cannabis News2 years ago

Cannabis News2 years ago

One-Hit Wonders2 years ago

One-Hit Wonders2 years ago

Cannabis 1012 years ago

Cannabis 1012 years ago

drug testing1 year ago

drug testing1 year ago

Education2 years ago

Education2 years ago

Cannabis2 years ago

Cannabis2 years ago

Marijuana Business Daily2 years ago

Marijuana Business Daily2 years ago

California2 years ago

California2 years ago