For more than a century, Harlem has helped define New York City’s world famous cannabis scene. From 1920s-era Jazz pioneers to the legal legends of today, Leafly honors the neighborhood’s deeply rooted influence on weed culture.

1914: New York begins restricting cannabis to medical use

1927: New York state prohibited the sale and possession of cannabis altogether

After more than a decade of medical-only laws, New York fully banned the plant in 1927. The law aimed to “remove habit forming drugs and assert control over narcotic drugs,” according to historians. There was still an exemption for “medical preparations made with cannabis sativa and cannabis indica when combined with other ingredients in medicinal doses.”

Related

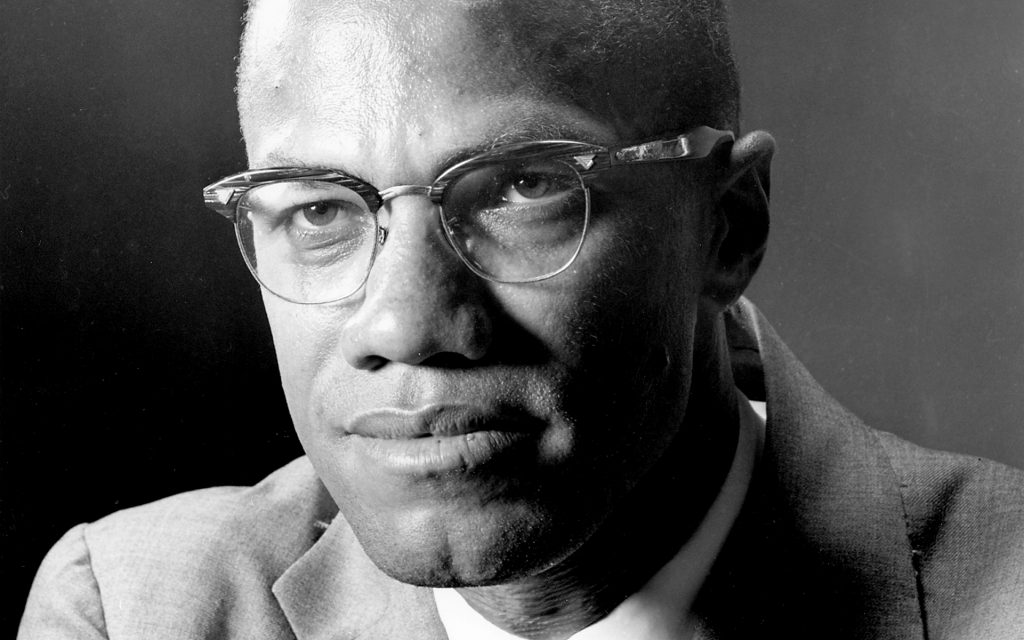

Malcolm X: From legacy cannabis seller to iconic activist

1920: Louis Armstrong was blowing loud

Jazz icon Louis Armstrong reportedly first tried cannabis in the 1920s and continued to use it throughout his career, including before performances and recordings. He referred to cannabis affectionately as “the gage.” The musician was an instrumental influence in Harlem’s rich Jazz scene during the early Harlem Renaissance.

When describing his relationship with cannabis to biographer Max Jones, Armstrong said, “We did call ourselves the Vipers, which could have been anybody from all walks of life that smoked and respected the gage… That was our cute little nickname for marijuana.” Armstrong added: “We always looked at pot as a sort of medicine, a cheap drunk and with much better thoughts than one that’s full of liquor.”

It is said that the jazz instrumental song “Muggles” was influenced by cannabis. Before the term “muggle,” aka a non-magical person, made its way into popular culture thanks to Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling, the term “muggles” or “mugs” had often been used by jazz musicians to refer to cannabis.

Related

Louis Armstrong and cannabis: The jazz legend’s lifelong love of ‘the gage’

1923: Harlem’s legendary Cotton Club is founded

Opened in 1923, the Cotton Club was originally located on 142nd St & Lenox Ave in Harlem. The club was founded and operated by British mobster Owney Madden. The previous establishment was called Club Deluxe and had been owned by legendary boxer Jack Johnson. Johnson sold control of the establishment to Madden but remained onboard as manager and the face of the club. Madden redesigned the club to serve minstrel shows and bootleg booze to New York’s white upper class.

Nate Sloan, who holds a PhD. in musicology from Stanford, studies “the largely forgotten racist history of a legendary musical venue.” Sloan points out that while Harlem’s top Black performers were the club’s main draw, Black patrons were not allowed to attend. The club was often decorated to resemble a plantation or jungle.

“Those upper-class white New Yorkers got their kicks ‘slumming’ in Harlem,” Sloan explains. Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, and Lena Horne performed there in time as the club evolved from serving New York’s bourgeois in the 1920s to the hip crowd of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s. Madden also used the Cotton Club as an outlet to sell beer during alcohol prohibition, and at times it was a safe space for artists and visitors to find and consume cannabis. Other legendary performers included Dorothy Dandridge, Adelaide Hall, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Ethel Waters, and Louis Armstrong.

1932: Cab Calloway’s ‘Reefer Man’

In 1932, Cotton Club favorite Cab Calloway released the song “Reefer Man,” which coined the slang term that some OGs still use when referring to the plant. Despite the growing popularity of cannabis in the 20s, laws became more stringent. In 1933, the Uniform Narcotic Control Law removed medical exemptions for cannabis use.

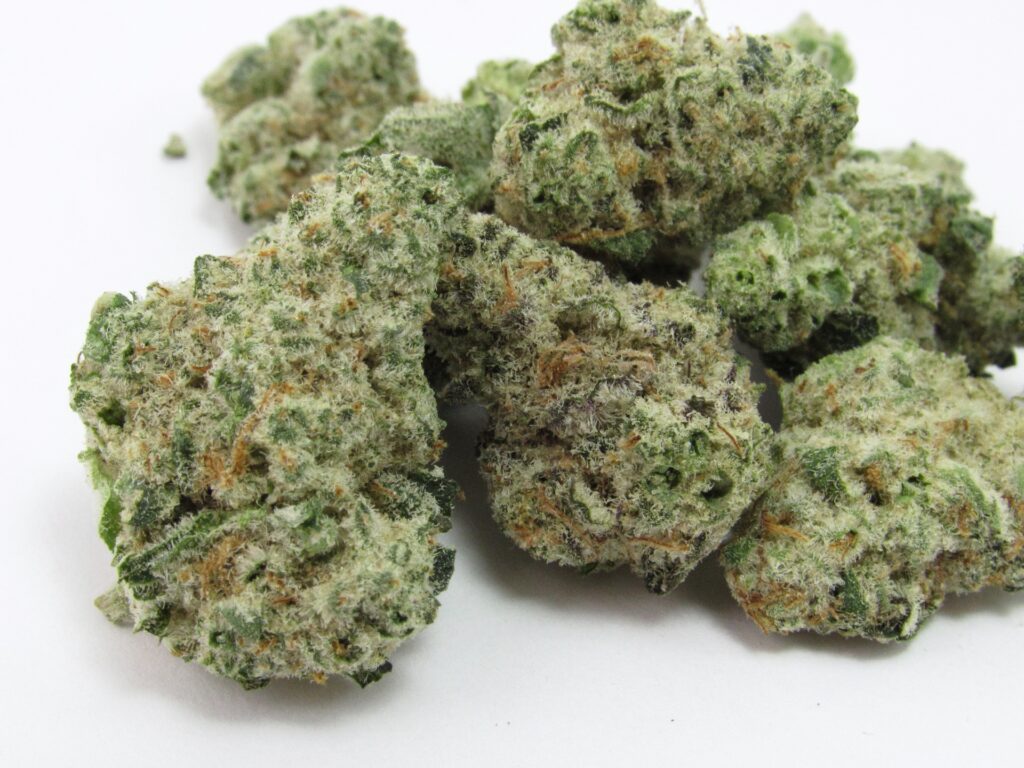

A report from the 1930s details anecdotes about cannabis from this era and speculates that there were more than 500 individual sellers and 500 “tea-pads,” or weed shops, in Harlem alone at the time.

“The common names for the cigarettes are: muggles, reefers, Indian hemp, weed, tea, gage and sticks… The ‘panatella’ cigarette, occasionally referred to as ‘meserole,’ is considered to be more potent than the ‘sass-fras’ and usually retails for approximately 25 cents each. The hemp from which the ‘panatella’ is made comes from Central and South America. ‘Gungeon’ is considered by the marihuana smoker as the highest grade of marihuana. It retails for about one dollar per cigarette… It appears to be the consensus that the marihuana used to make the ‘gungeon’ comes from Africa. The sale of this cigarette is restricted to a clientele whose economic status is of a higher level than the majority of marihuana smokers. A confirmed marihuana user can readily distinguish the quality and potency of various brands, just as the habitual cigarette or cigar smoker is able to differentiate between the qualities of tobacco. Foreign-made cigarette paper is often used in order to convince the buyer that the ‘tea is right from the boat.’ There are two channels for the distribution of marihuana cigarettes— the independent peddler and the ‘tea-pad.’ From general observations, conversations with ‘pad’ owners, and discussions with peddlers, the investigators estimated that there were about 500 ‘tea-pads’ in Harlem and at least 500 peddlers.”

Wiiliam H. Johnson’s Historic account of Harlem’s 1930s cannabis scene

1937: National ban on cannabis begins decades of federal prohibition

In 1937, Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act, which explicitly criminalized cannabis. At the same time, the New York Academy of Medicine issued a report declaring marijuana did not induce violence, or insanity, or lead to addiction or other drug use, as the 1936 film Reefer Madness claimed.

Related

America’s war on drugs has been racist for a century

1940s: Malcolm Little smokes and sells weed in Harlem before becoming Malcolm X

In his autobiography, Malcom X (born Malcolm Little) intertwines hazy descriptions of his first experiences smoking “reefer” with hazy memories of dance parties at the Roseland Ballroom, shooting craps, playing cards, and betting with a pool hall friend named Shorty. “All of us would be in somebody’s place, usually one of the girls’, and we’d be turning on the reefers making everybody’s head light, or the whisky aglow in our middles,” he wrote.

1950s: New York drug treatment programs derailed by racialized Drug War

During the 1950s and 1960s, heroin addiction across the US prompted concerns. As a result, New York passed progressive laws to support those battling heroin addiction. Cannabis, labeled a narcotic, was closely associated with heroin, despite sharing little similarities with the substance.

But New York’s rehabilitative push was short-lived. Instead, new laws instead aimed to punish drug users and sellers. The passage of the country’s harshest drug laws to date, the Rockefeller Drug Laws, came in 1973. Historians say, “In large part, the criminalization of Black drug users and dealers in New York City drove this punitive turn. By looking at New York state’s response to heroin in Harlem during the 1960s, we can better understand how racialized narratives about drug addiction impact policy.”

After World War II, heroin use spiked throughout the country, and Harlem became a central point for its distribution. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics reported that in 1964, an estimated 48,525 “active addicts” resided in the country, half of whom were believed to live in New York City. Harlem was referred to as the “Dope Capital” of the nation.

1969: Summer of Soul is the Woodstock of West 125th Street

Despite legal issues and social stigmas surrounding cannabis, the people of Harlem continued to use the plant with pride. 2022 Oscar-winner “Summer of Soul” documented the ways in which cannabis catalyzed cultural change and innovation during the time.

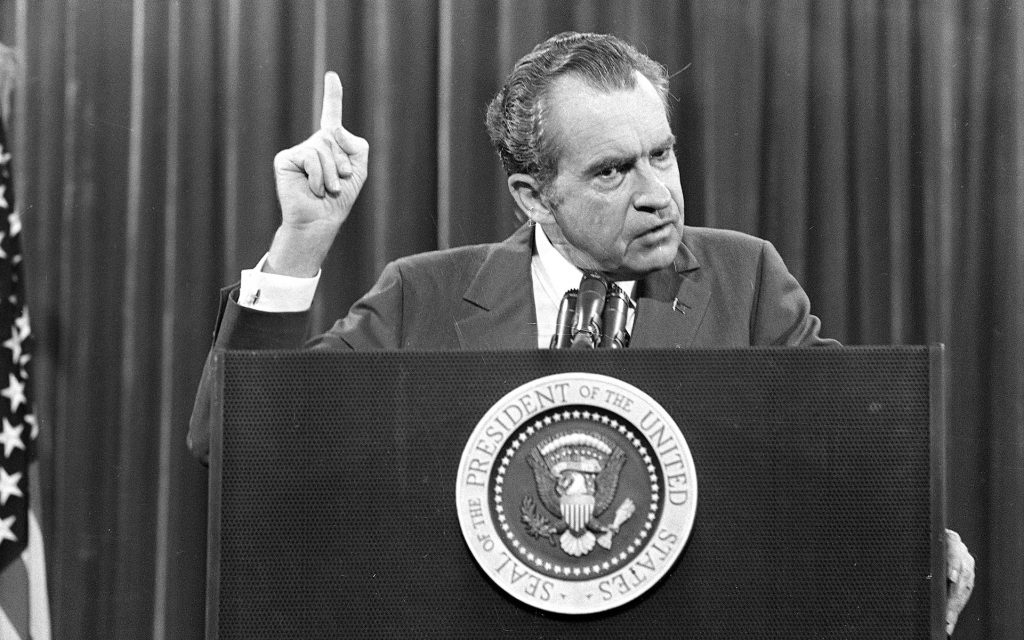

1972: Nixon declares Drug War, targets ‘Blacks and Hippies’

In the early 1900s, marijuana was used to justify violence and discrimination against Mexicans by border patrol agencies. Then in 1968, the Nixon White House identified two groups as domestic enemies: the antiwar left (hippies), and Black Americans. The administration decided to use drugs to declare an uncivil war. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war, or Black. But by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin… And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders. Raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

John Ehrlichman, former Nixon domestic policy chief (2016), Harper’s Magazine

1980s: Weed influences seeds of Hip Hop

Harlem was a hotbed for the growth of early Hip Hop culture, and while cannabis wasn’t much of a topic on the records at the time, it was widely used by popular musicians and dealers. In the video above, Fab 5 Freddy, who hails from Brooklyn, explains the essential role that Harlem legacy dealers played in New York’s cannabis culture.

Related

The 23 dankest lyrics about loud weed

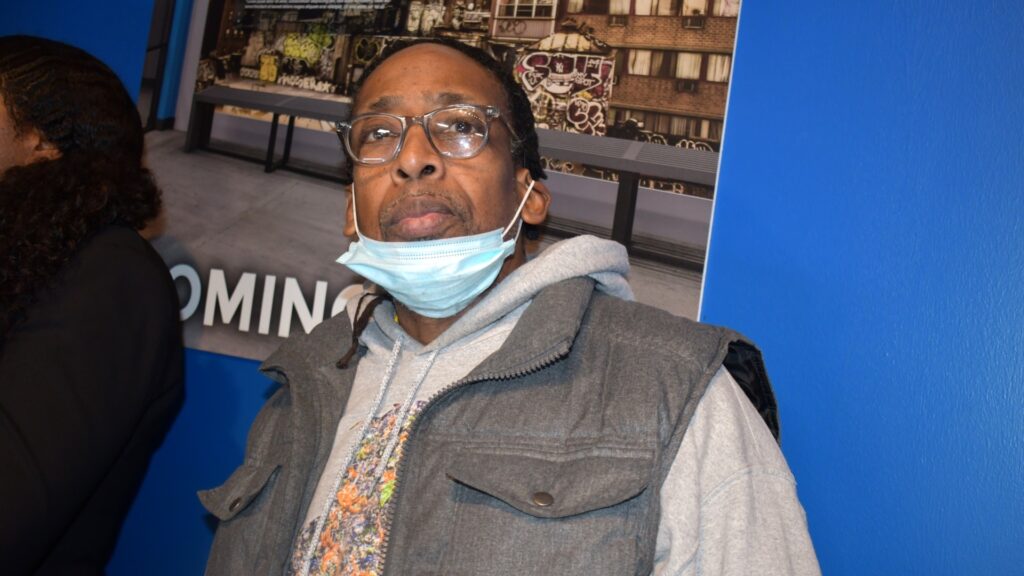

1990s: Rappers make an underground legend notorious

Initially working out of a candy store-slash-juice bar in Harlem, Branson was a major conductor and distributor of high-grade marijuana and hash oils in NYC during the early 90s. Operating in the thick of the War On Drugs, Branson was one of the rare standalone plugs that celebrity smokers visiting NYC could count on to deliver good gas. Hence the chronic name drops on songs from East Coast rappers like The Notorious B.I.G., The LOX, Nas, and Redman himself (read more classic lyrics about Branson below).

Related

The NYC legend behind Redman’s 20-year-old stash of Branson buds

2000s: Diplomats and Purple City brand Piff and Purple Haze

In the 2000s, legacy pioneer Shiest Bubz made his name in music with his Piff brand, mixtapes, and by founding Purple City Productions, which contributed heavily to New York’s underground mixtape scene and the careers of artists like Smoke DZA.

Bubz worked with Harlem icons Cam’ron, Jim Jones, and Juelz Santana, all three of whom are poised to follow in his footsteps as they venture into the legal cannabis industry. Bubz and company’s influence is well-documented in DVDs and tapes that once circulated nationwide. Some videos still live on YouTube and provide background to those looking to understand how guys with names like Shiest Bubz and Luka Brazi became the top dogs in New York’s budding cannabis industry heading into the 2020’s and beyond.

Just under a decade since medical cannabis returned to New York in 2014, and nearly two years since adult-use was legalized, Harlem continues to stand at the forefront of New York’s world-famous weed culture.

By submitting this form, you will be subscribed to news and promotional emails from Leafly and you agree to Leafly’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from Leafly email messages anytime.